Written by: The Readeress editorial staff

Translation: Tom Atkins

editing: Shlomit Cnaan Aviram

“I Love Rehearsals, but it’s about time to put it out there: Erez Drigues’s public presence is fucking triggering me,” journalist Ofir Sgerski wrote in her personal Facebook page on January 29th. In her post, she goes on to describe how Drigues would send her “sleazy messages,” despite her requests that he stop. “Apparently, I wasn’t the only one. In interviews he says it’s not criminal, and he may be right,” she writes. ”He says it’s sleazy and pathetic, but it’s not only that – it’s also offensive.”

Erez Drigues? More like triggers lol 🙁 “I Love Rehearsals, but its about time to put it out there: Erez Drigues’s public presence is fucking triggering me. That includes the

character he plays – Tomer, a toxic man who wins his ex back by selfishly crashing her big night, which is framed as a sweet romantic ending.

And yes, I might be finding it a bit difficult to separate the man and the character because Drigues used to send me sleazy messages, completely disregarding my clear signals that they were inappropriate. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one. In interviews he says it’s not criminal, and he may be right. He says it’s sleazy and pathetic, but it’s not only that – it’s also offensive.

Seeing a character like that puts me back where I was when I was deeply hurt by another man, beloved by the industry. When I would tell people how he treated me, the response would often be “Really? But he’s so cuuuuute.”

My point is: ease up a bit on your admiration. You don’t really know who the people on the screen are, and you don’t know who you might hurt with it.”

A torrent of heated reactions, on both sides, followed the post. Among accusations of destroying Drigues’s career, destroying romance and destroying mankind in general, more testimonies emerged, by other women who, like Sgerski, had been harassed by Drigues. The vast majority contacted Sgerski privately, sharing stories of similar harassment aimed at them by the theater director and creator of the beloved show. Sgerski aired these in another post, meant to clarify the first one’s somewhat vague tone:

Some people have said that my last post, about Erez Drigues, wasn’t clear enough, that I was blowing things out of proportion and that you can’t shame every douche-bag.

So first of all, there’s a difference between shaming and reacting to things a person admitted to in interviews and described doing.

Second, sending women sexual messages without their consent is sexual harassment, not “mere douchery.’’ In fact, I specifically didn’t use that term in the previous post because I didn’t want to antagonize anyone, and because I thought it was important to be gentle with someone I still have a lot of professional esteem for, someone who, together with his creative partner, Noa Koler, brought such wonderful TV moments to my screen.

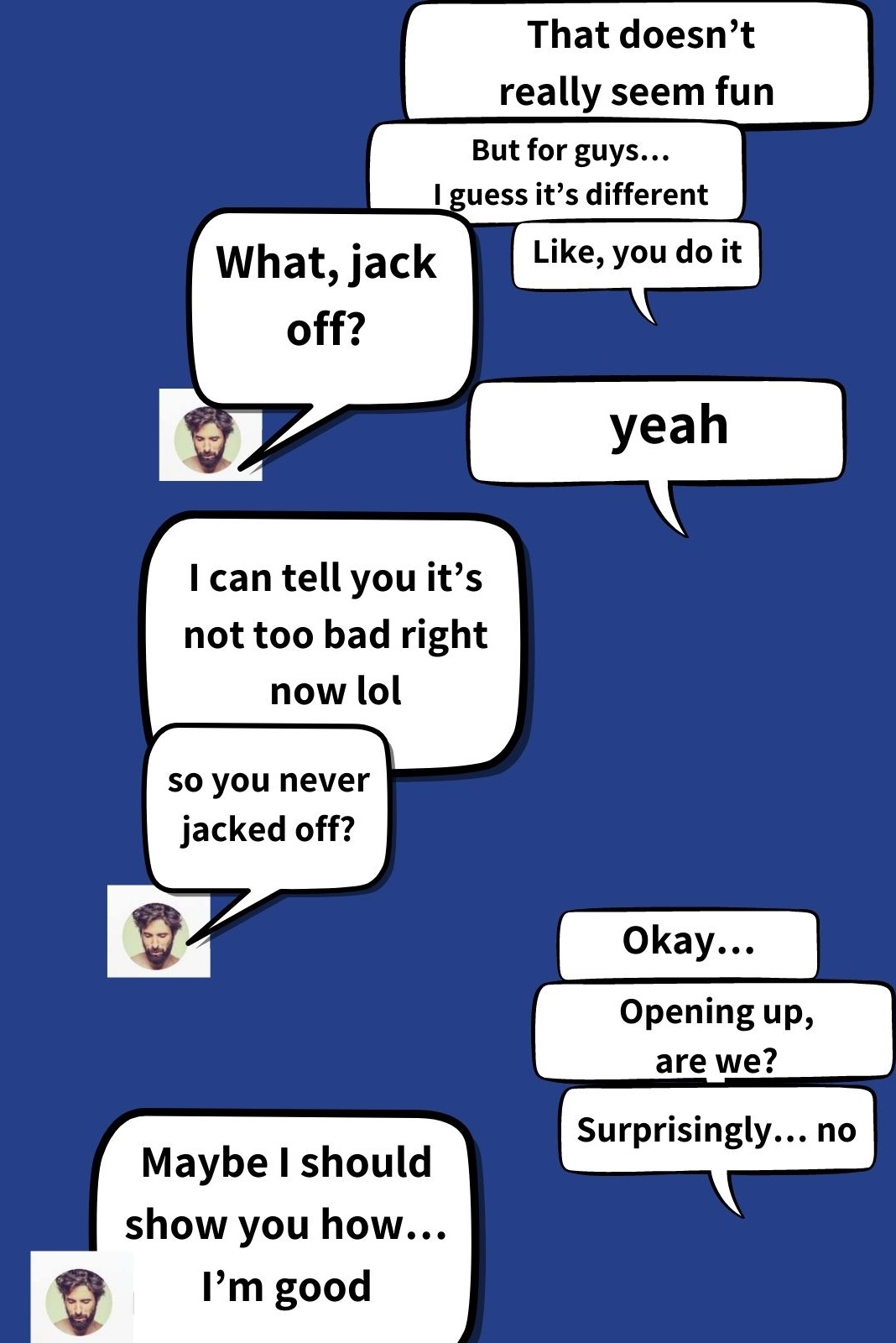

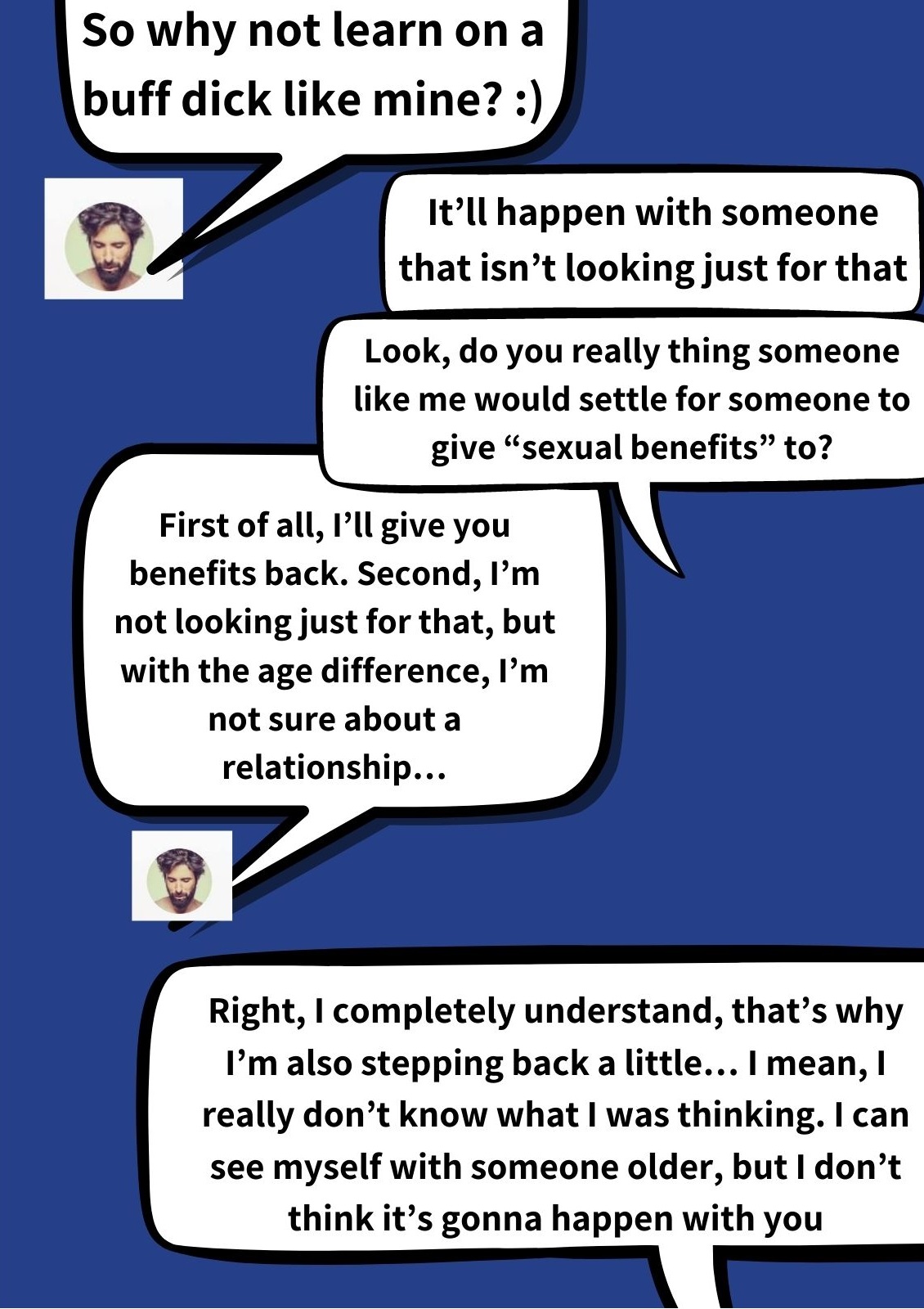

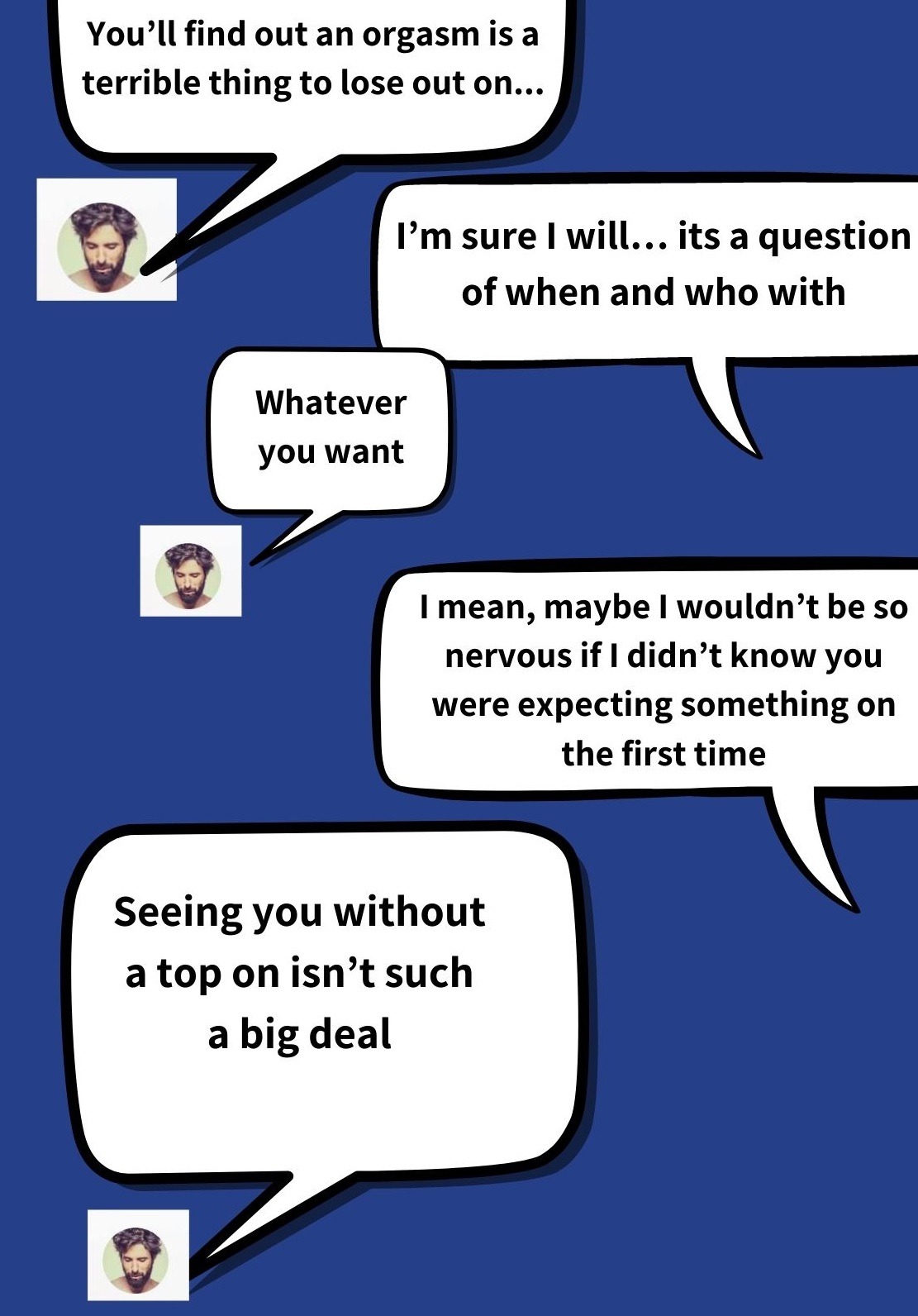

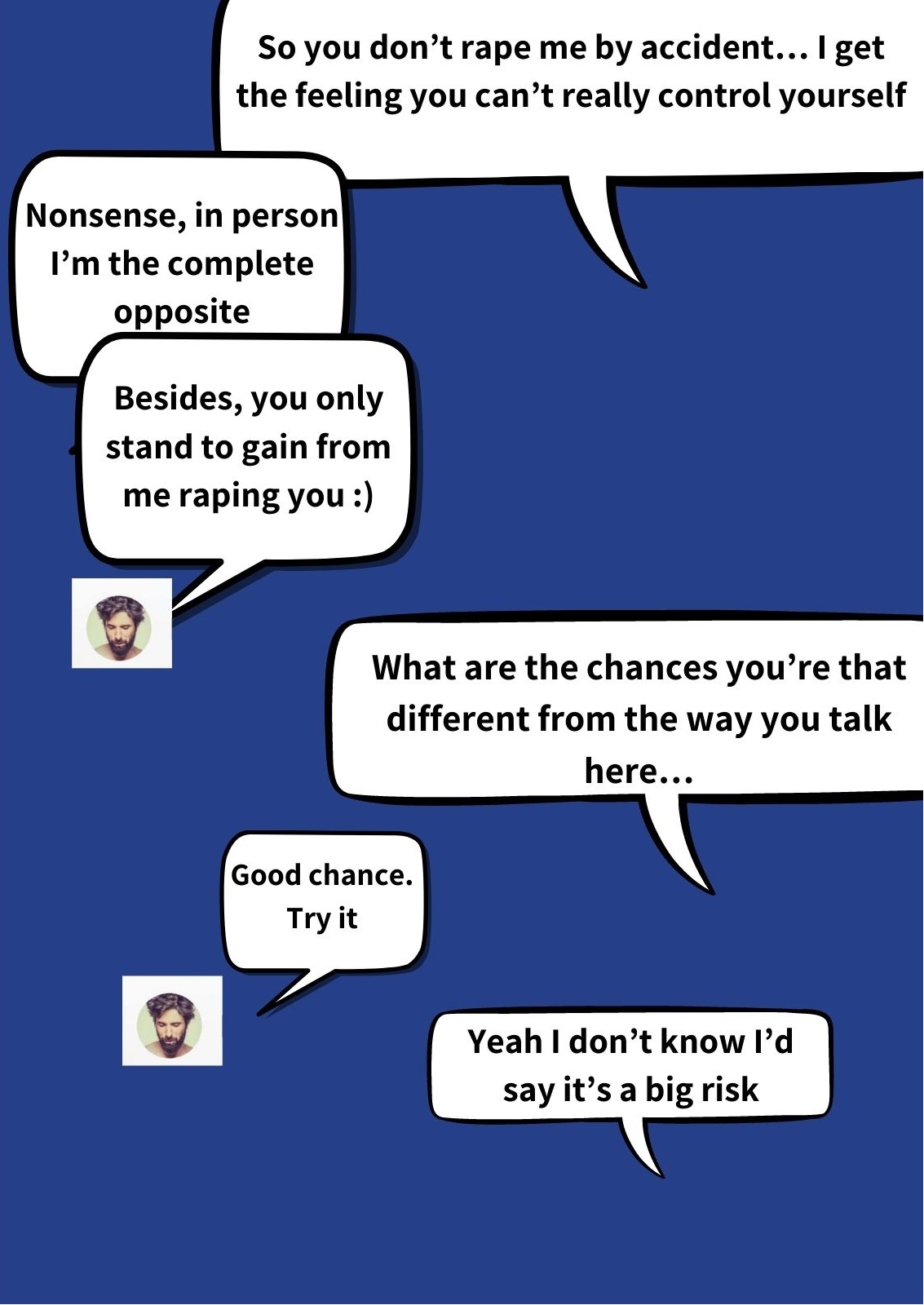

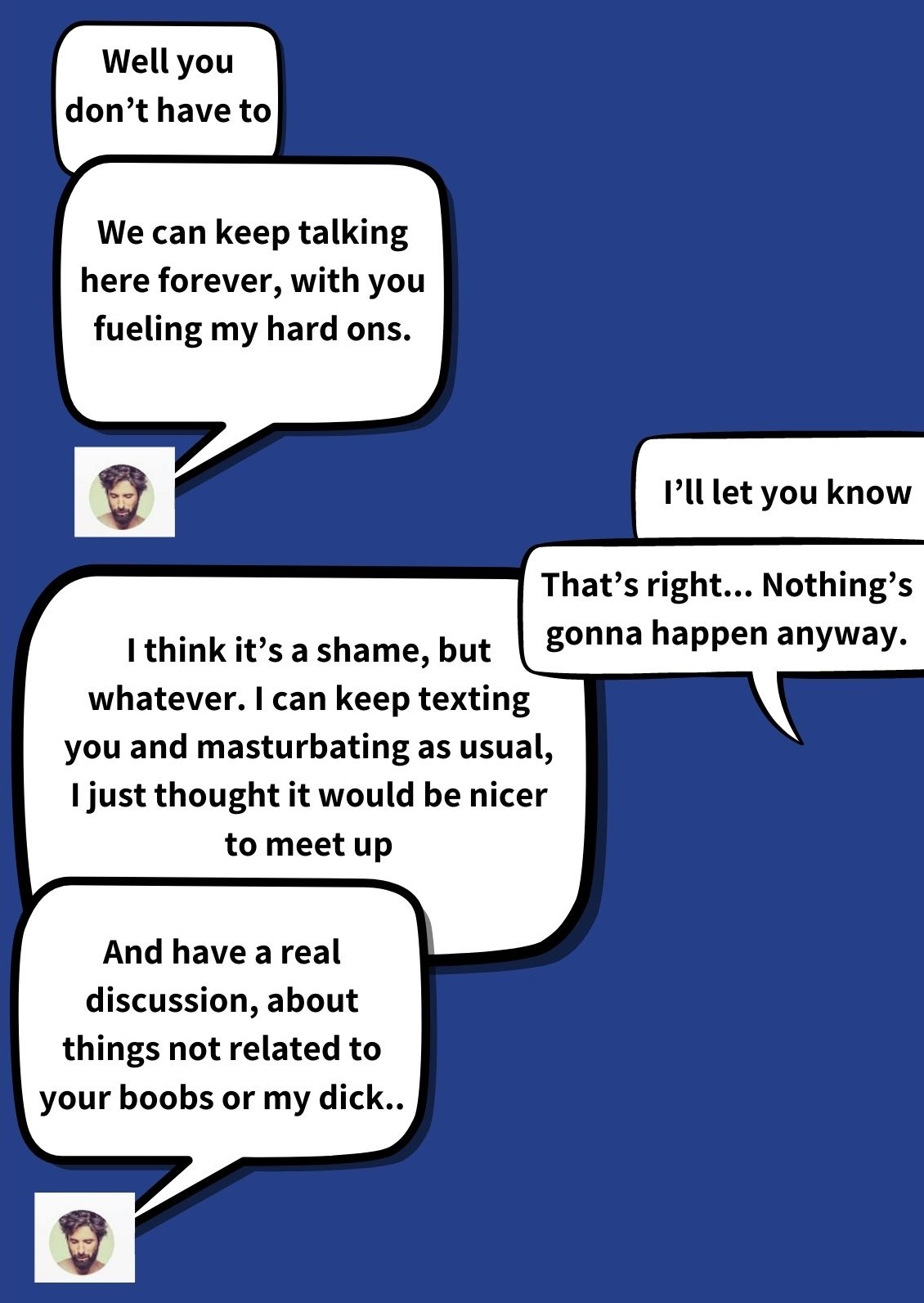

Now, as a special service for those of you who are having difficulties understanding the situation, here is a collage I made of messages women sent me after my last post. It doesn’t feature all the women who reached out, only the five who agreed for their conversations to appear in it. Any identifying details have been blurred, at their request.

Also, as some thought I was too harsh, I added some care-bears.

The responses to Sgerski’s second post left no doubt about it: behind each seemingly isolated report there were other victims, revealing a repeated pattern of harassment and then silencing. Some of these women said they enjoyed the show, and even saw characters like Tomer and Ofer as Drigues’s way of admitting his past misconduct towards women. But in interviews, they were disappointed to discover he still denies having crossed the lines, labels the whole saga “pathetic” and “sleazy”, and doesn’t consider for one moment how damaging his actions were.

Erez Drigues’s case makes it clear that in theater, as in other cultural and professional areas (such as poetry and academia, as we recently discovered with the cases involving Roy Chicky Arad and Haim Dauel Lusky), women are expected to overlook the misconduct of powerful and influential men. If they dare to resist, their professional future is on the line. Even if Drigues’s text messages aren’t sexual harassment in the legal sense, it’s still behavior that actively fosters exclusion of women, preventing them from advancing, or at least from feeling comfortable in their environment. The academic term is chilly climate, a feeling of uneasiness in the space in which you operate.

Due to this concern, this report contains testimonies by only four of a significantly higher number of women. Some of the stories we heard include gross abuse of authority, and demonstrate just how women often face more than solely professional obstacles, in their struggle for work-place equality.

“What’s Up? Still a Virgin?”

“I was 17, perhaps only 16, and it lasted for three years! Three years of non-stop messages and harassment,” says Dar (unless specified otherwise, all names have been changed). “Thank God, even at that age I had some sense and didn’t agree to meet him, as much as I idolized him. He didn’t care how young I was. I don’t want to know what would have happened if…”

Dar studied theater at high school. She met Drigues, who was 30 at the time, on a school visit to the Yoram Lownshtein Performing Arts Studio. Drigues was an acting instructor at the studio. He made a strong impression on the eager theater student. Following the visit, Dar sent him a Facebook friend request. The screenshots she sent us show that Drigues immediately knew who she was, knew how old she was, but still implored her to fulfill his sexual urges.

Today, Dar is ashamed and embarrassed that she continued messaging Drigues, rather than blocking him the moment he started making the conversation sexual. She was a teenager then, but older women have also been drawn into long, uncomfortable conversations with him.

“I’m Just Offering to Take Care of You”

Inbar was harassed by Drigues in 2016. She’s not in theater, but works in related fields. At the time she was an avid theater enthusiast. “I was a dumb 24-year old, and I idolized anyone who had anything to do with theater,” she says. Drigues approached her on Facebook. At first, she was excited that such an esteemed creator contacted her. A few moments later, not so much.

Drigues offered to “take care of her” in various ways, using what is apparently a popular euphemism with sex offenders. “At one point I just started to ignore him, because my attempts to move the conversation towards getting to know each other weren’t really working.” she says.

“I can definitely say it took me time to work up the courage to watch Rehearsals,” Inbar admits. “For the first episode, I had to start over three times before I could see it from beginning to end. And it wasn’t easy to cope with all the praise it got.” This point Inbar makes is important because it explains why these women “have suddenly remembered” to speak up now: When you don’t see or hear much of the person who hurt you, it’s easier to leave the injury behind. When he’s splashed on every screen and newspaper on a daily basis, wrapped in love and adoration, it’s hard not to wince in pain.

Another testimony comes from Tslil, a young actress whom Drigues harassed three years ago. “I saw a play of his in the Tzavta theater and had some questions about acting and directing,” she remembers. “I was a first-year acting student at the time. I was naive enough to think I could just approach him on social media.”

She messaged Drigues on Facebook, and their conversation quickly turned from professional to very unprofessional. “Drigues offered to meet. I refused,” she says. “He complimented my appearance and started telling me how ‘horny’ he was, told me where his hands were and what they were doing, and even sent me a picture of his crotch. He was dressed, but it was still unpleasant and unsolicited.”

“I told him I was uncomfortable with the direction the conversation was taking. He apologized, but said it was because he was constantly horny and masturbating. I ended the conversation. I felt humiliated and disgusted, and racked my brain trying to understand how any of my questions implied that was the kind of communication I was interested in. I still don’t know.” Tslil was so uncomfortable with the conversation that she deleted it, which is why we can’t show any screenshots of it.

“A few years later I told a friend about it, and she said something similar had happened to her,” Tslil shares. “Apparently he’s a serial offender. Everybody knows, it’s a thing. Plenty of girls, mainly in theater, know about it.” Tslil emphasizes that even though the Drigues phenomenon is well-known, it’s far from the only one in the field. “There are much, much, much too many sleazeballs like him in this field,” she says. “I wish I could give the name of every guy who has ever harassed me. Just put it out there with their picture. There are just too many.”

“Chilly Climate”

“Chilly Climate”

Even if Drigues never physically assaulted anyone, he made sure to create an unpleasant atmosphere, in which women had to contend with his crude and harassing messages, or risk hurting their careers.

That’s what happened to Noy, a young theater creator. She rejected Drigues as carefully as she could, but her career still suffered because of it. She met Drigues five years ago, as a teenager. “I saw a play he was on in the Haifa theater, and I absolutely idolized him,” she recounts. “After the show I went to the stage door, to tell him how much I liked the play. I saw him walking in the middle of a huge mass of girls, all of them my age or younger. Something about it really disgusted me, so I walked away.”

Two years later, at 19, Noy happened to see a post Drigues wrote about his new play. She gave it a Like, and Drigues sent her a friend request and started messaging her. “In my stupidity and admiration I thought he had something to say about my writing,” she says, with a considerable measure of self-flagellation. She had a good reason to think that: at the time she had submitted texts to a project Drigues was heading. “Apparently it wasn’t my writing he was interested in,” she says.

“Very quickly, and very aggressively, he started signaling he was interested in me. I tried rejecting him super-gently, so it wouldn’t hurt my chances in the project. A few months later I was rejected for the project, and a few days after that he started messaging again, asking if I’d changed my mind.” Noy answered that she had a boyfriend, and says Erez was angry about that answer. “He started interrogating me, was angry that I had a younger boyfriend,” she says.

But the real revenge came two years later, when Noy accepted a certain role in the same annual project, and had to work under Drigues, a year after their last encounter. “It was very awkward,” she says. “It was little things, so I could never know if he had anything to do with it or if it was a coincidence.” This confusion is shared by many of the women we talked to. They feel their career was hindered after they rejected Drigues – but in elusive ways, too subtle to put a finger on.

Still, Noy is able to point to a few irregularities: “For example, I was the only one not listed on the poster or anywhere else where the festival was mentioned,” she remembers. We checked, and while other people who had identical roles to Noy were credited, she was left out.

“Whenever I texted him about something, or even talked to him, he wouldn’t answer. The director and producer [both women] couldn’t understand why I ”switched off” whenever I was near him. I told them, and they helped wherever they could.”

Noy says watching Rehearsals was complex for her. “It’s so complicated,” she says. “On one hand it’s an amazing show, and it has so many amazing people who aren’t him, and you watch it with friends, and everyone watches it, so am I supposed to be the downer who doesn’t? It’s not every day someone makes a show about theater… on the other hand, it’s difficult to see him. Unpleasant. I watched it with my partner. He knows everything about what happened, and we were both very ambivalent.”

It’s a Pity That Offenders Don’t Spend a Tenth of the Energy the Victims do, Thinking About the Other Side

Many of the women Drigues has hurt along the years describe a difficult internal conflict while watchingRehearsals. On the one hand, they enjoyed the show. On the other – they had a hard time coming to terms with the love the media lavished on Drigues. They felt guilty for “being overly critical” of his work, and this feeling, alongside the fear of conflicts and ricochets, prevented them from speaking, until now.

But underneath the surface, in one-on-one conversations, Drigues was revealed to be a serial offender. “In the last few years I heard multiple accounts of him being compulsively sleazy and harassing,” says Anat, a theater director. From the moment the show was first aired, I kept thinking, “When is it going to blow up? It’s just a matter of time”.”

While Anat expected the scandal to explode, she was surprised at the scope. “After Ofir [Sgerski] published her post, I was surprised to find how many women he had hurt,” she says. “I had no idea how big this was.” While she was pleased that it came to light, she is also sorry for her colleague. “One feels a lot of pain and sadness for a very talented man who, at such a wonderful and important phase of his career – tripped himself up,” she says.

Anat says that even today, in the so-called #MeToo era, it’s hard to bring this kind of offense to light, because victims still face accusations from every direction. “We have to understand that it’s a very complicated situation. I highly doubt that any woman finds pleasure in it,” she clarifies. “Many women were very careful about deciding whether to expose their experiences or not, specifically because they didn’t want to shame him, or “publicly hang” him – both out of a sincere appreciation of his work, and so they won’t be perceived as being out for revenge, as populist, or as envious of his success and the show’s. I wish Erez, and so many other men in theater, were that sensitive. Many still harass regularly without having even a tenth of that consideration or thought for how the other side is feeling, either before or after the fact.”

Women Told Me “Watch out for That Actor,” “This One Can Get Handsy.”

Noa Wagner is a director and a member of the Israeli Women Theater Creators’ Forum, and also the only interviewee who agreed that we use her full name. She says that immediately when she entered theater, she was exposed to a culture of both sexual harassment and silencing. “Women told me ‘watch out for that actor,’ ‘This one can get handsy,’ and even ‘that’s how it is around here. It used to be worse’,” she says. “That’s how people talked. women would tell you privately so you’d know to take care of yourself. They knew that saying it out loud wouldn’t do any good.”

The way Wagner sees it, sexual harassment is widespread in theater – but not more than in any other field. She does admit that its harder to discuss in the entertainment industry, for a number of reasons. “It’s a small industry – everyone is friends with everyone, everyone knows everyone,” she says. “There’s concealed intimidation, and there’s an uncomfortable feeling that creates a culture of silence.” Another possible reason that women keep silent about harassment is an antiquated school of thought according to which “The director is a dictator.” This school, Wagner says, asserts that “you have to accept everything the director does or says.” Trained to be completely obedient, actors withhold their voice even in the face of conduct that crosses professional boundaries.

But is it even possible to set such clear boundaries in the world of theater? Wagner finds it a difficult question to answer, but clarifies that directors, men and women alike, have to be very attentive to their inner compass, which they hopefully possess. “As a director, man or woman, you hold great responsibility over your actors,” she says. “When dealing with sexuality, you have to be very professional with your intentions.”

It’s important to note that many incidences of harassment in the entertainment industry, such as those presented here, are in a “gray area”, and only seldom manifest as a real physical assault. Be that as it may, this “gray” harassment also has severe mental and professional repercussions for victims. Often, they are afraid to complain – in such a small industry everyone knows everyone else, and your ability to advance depends on what people think about you.

“You Just Have to Say the Wrong Thing, and Someone More Powerful in the Industry can Change Your Future”

“It feels like you just have to say the wrong thing, and someone more powerful in the industry can change your future.” Wagner says. “I’m not as scared of it as I used to be, because I know its hard for me not to follow my heart. It takes a greater toll on me. But I used to be scared, and I didn’t want to be seen as a victim. You don’t want to be remembered for talking about this man or the other, or be the one who went through this or that. you want to be appreciated for your work, your abilities, your directing.”

Besides the conflict with the outside world, Wagner describes an internal conflict harassment victims find themselves in. “You keep asking yourself why didn’t you react in time, why you only bring it up now,” she says. “Women can get confused – we’ve been sexual objects for years, it was part of the norm, so it’s rooted in our minds as well, not only in men’s. sometimes the injury is complicated in itself. If someone attacks you on the street, in a dark alley – that’s clearly wrong. But you can’t always say what’s wrong with the way a director or an actor came too close, or put his hand on your shoulder.”

Many women share the fears and concerns Wagner describes, partly because of the accusations so often leveled at sexual assault victims, accusations which easily become self-accusations. Before even making a complaint, suing or even speaking out, you already accuse yourself of being an “attention seeker”, of holding grudges of taking things out of proportion, of being obsessive and whiny. Or, as Tslil described – you first scrutinize what it was about your behavior that caused the offender to behave as he did.

Exposing harassers’ behavior patterns is a step on the path to cleaning our culture of sexism – but it is also a step on the path towards healing for many victims who can finally stop blaming themselves.

Erez Drigues’ response:

Ofir Sgerski’s post, written following my Yedioth Ahronoth interview, brought to the surface a behavior of mine, one that has hurt her, one that has hurt others. I’m aware of it, I understand it well and therefore, even before her post, I took every step required to change.

Part of this change was writing Rehearsals, which has brought embarrassing and inappropriate aspects, about which I am sorry and ashamed, to prime-time television. As part of this change I also revealed, in the same interview, some of the messages shown here.

It is a personal process. It is still ongoing and I hope that, in due time, I could also apologize to those I’ve hurt. I do, however, want to emphasize that I have never allowed any personal matter to influence professional decisions. I never will and I categorically reject any implication otherwise.

Headline photo: a screencap from Rehearsals, Kan 11