Translated by: Amit Meyer

I was born in Rishon Letsiyon, in the neighborhood of Ganei Esther, on the coastal city’s eastern side. When I was four, we moved to Mishor Hanof, a developing neighborhood for the new Israeli middle class that emerged in the 1990s. We built a house from scratch. In that big house in Mishor Hanof, I laughed, I cried; that’s where I ran away from and that’s where I returned to. That was where my mother taught me sewing and cutting, painting on walls and writing. There, my younger sister would run around with her blankie and pacifier. There, my older sister got ready for her wedding, dresses were sown, festivities were celebrated. There, we would stay glued to the TV at times of war, and when that horrible time came, that was where we took care of my dear mother who fell ill. There, we hugged, cried, clutched the sofa in fear. There, we still carry on the traditions she had taught us. And damned be anyone who dares telling us, “Why don’t you move?”

This personal place is where I start from in writing this text, which is sure to draw some harsh reactions. Just like everyone else in Israel, I’m watching the TV networks, which keep on reiterating the narrative by which the latest wave of Arab violence erupted out of thin air. Their disposition toward violence just exploded like that. They can’t be trusted. Arabs, mentality… There isn’t really a need to repeat all that. And when someone in the studio even tries to explain where that unbearable violence came from, they cut to commercials, or even worse, hurl at them: “But do you c-o-n-d-e-m-n?” There’s no room to hear the actual story, to decipher what that violence is rooted in, and so, every time it boils over we’re just taken aback, surprised by it.

On Thursday night I was mind-boggled watching Moav Vardi, a journalist I truly appreciate, interviewing Knesset Member Aida Touma-Sliman. She unequivocally condemns the violence and, when asked about the reasons for it, provides a clear explanation. When she’s done going through it, Vardi, in a verbal juggling act, takes a long time to press her on semantics: But do you understand the reason? And if you do – do you justify it, then? But how can we understand? Is there nothing else in play here? He asks, hinting at some mysterious unknown. Perhaps the aggressive Muslim beast that lives within each and every Arab. Touma-Sliman responds well, sprinkling condemnation of violence after every other word, because she knows that’s what is expected of her at this time. She reminds Vardi that he already asked her about the reasons, and there were her answers. And understanding violence does not mean justifying it. They end their conversation respectfully, and I’m left confused. What did I just see?

And so we wander, between times of war and calm, oblivious and with eyes shut. I can understand that; if we open them we run the risk of acute sadness. But if we open them, we may also find an opportunity to correct injustices before the frustration simmering below the surface erupts all over again. And if we don’t make amends, at least we won’t be so shocked and surprised next time a wave of protests emerges.

The way I see it, the whole story is one about home, and that’s the story I want to tell. I chose four cities that have become flash points of the latest unrest, but also have a room deep in my heart. Acre, Lod, Haifa and Jaffa are all cities I know and love intimately; four mixed cities tied closely with the oh-so-pretty term, “co-existence,” which the past days revealed just how deeply fake it is.

This text doesn’t include the story of Sheikh Jarrah, which Liron Cohen, “Political Homeless,” wrote about so well in the Hebrew edition of this publication, where she also foresaw the flare-up that has engulfed our cities. It also leaves out the stories of Palestinians in the Gaza Strip and in the West Bank. But while mainstream Israeli media outlets go out of their way time after time to make a definite distinction and draw a clear line separating between “Israeli Arabs” and the Arabs of Gaza, I propose drawing a different line, the one that connects them.

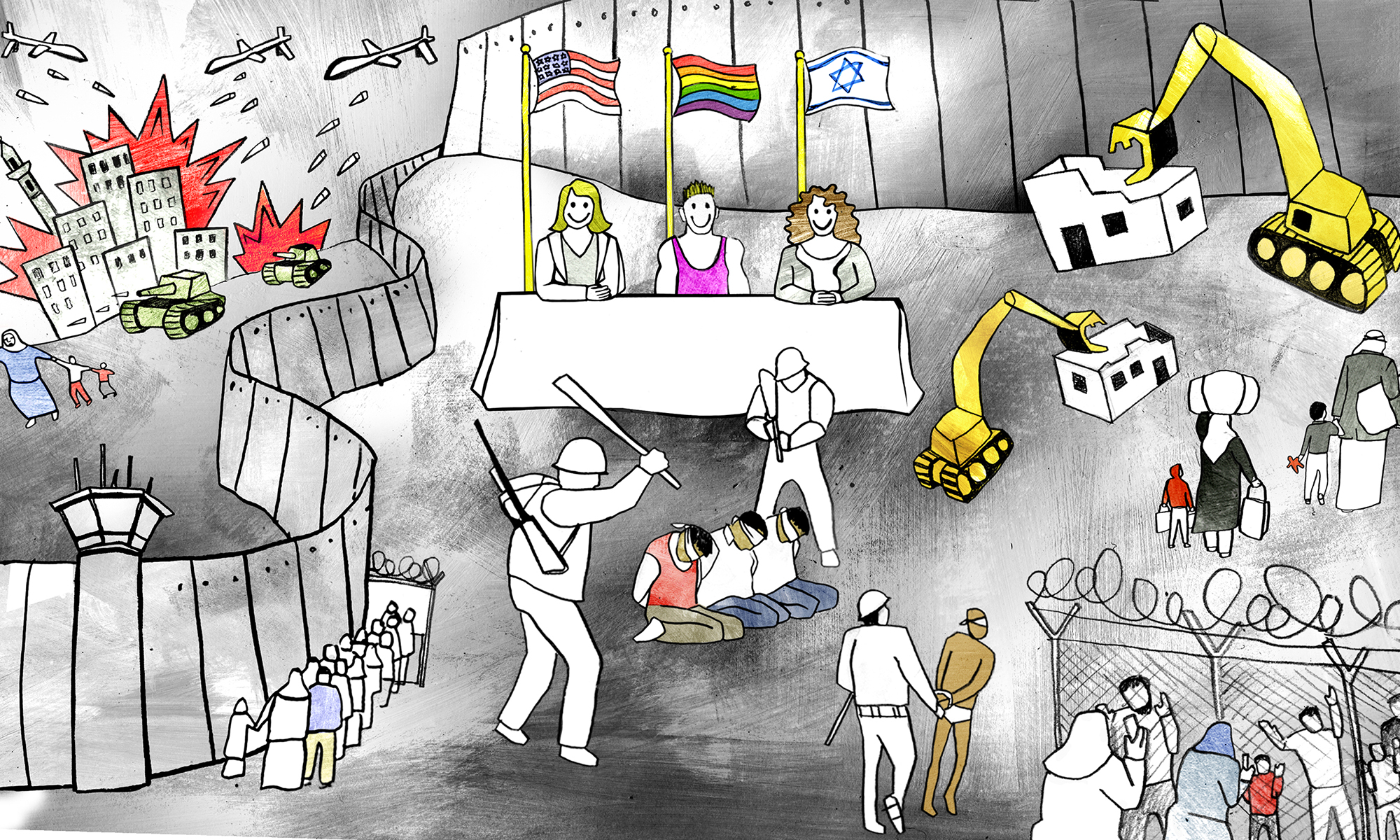

Apart from the fact that they are part of the same people, and in some cases even family, they all undergo very similar processes, with varying intensities and forms. What happens in Sheikh Jarrah – a wild no-man’s-land – is at the very core of the connection between Arab citizens of Israel, living under Israeli rule and dispossessed of their homes by force of law and gentrification, and between Arab residents of the West Bank and Gaza, living under blockade and deprived of their independence and freedom by force of arms. The collective Arab trauma spares no one, be it inside Israel’s borders or outside the territory it claims. It is this very trauma that moves and shakes, and at times inflames, the roots of both the Israeli and the Arab condition as one.

עכו عكا Acre

Over the past 12 years I’ve been looking very closely at Acre. That’s where I spent my gap year and that’s where I returned to five years later, to study for a degree I have yet to complete, and so, every year I pop up again at the college to take another course or an exam, and mostly, to be honest, to visit the Old City. Four years ago already, I sat down with one of the Arab women of the Old City, an activist with an Arab-Jewish peace group. She told me a story of Acre I’ve never heard before. In those days, protest banners decorated the city’s streets; it was at the height of the conservationist development. “Acre is not for sale,” read the posters, which were not touched on by any Hebrew media.

The majority of Acre’s Arab residents fall under the definition of “internally displaced persons.” In 1947, as the war started, Arabs living in the country fled/were expelled; some ended up in other Arab countries, some gathered in cities that became part of the newly founded Israel but held on to their Arab character, like Nazareth, for example. Some found refuge in the old parts of cities that would become emblematic of that co-existence, and these are Acre’s Arab residents.

Acre, a minuscule peninsula stretching out into the sea, needs only one look to reveal its story: It is one of the world’s oldest port cities, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001. A supposedly exciting matter became a primary, official source of the processes of dispossession in place there to this day. In order to understand that, we must return to 1948. In those days, the Palestinians who came to Acre were granted formal status by the State of Israel, equal citizens, supposedly. The homes they were evicted from/fled were expropriated; the homes they got to became their formal residence, but they were never theirs. The houses in Acre’s Old City are under the auspices of the state, that is, managed by state-owned housing companies like Amidar or Halamish, so that anything these Palestinian residents want to change in their own home requires bureaucracy and approval. It sounds like it makes sense. After all, these houses are historically important conservation sites. But take a closer look and you’ll find the bureaucratic hurdles faced by families who want to add a room for a child who grew older or fix their crumbling balcony aren’t the same hurdles faced by developers – tourism professionals and rich investors who came to Acre, realized what exciting potential it has, and got to work. And by work I mean textural changes, structural changes and all sorts of very extreme changes that clearly violate the very strict regulations for listed buildings. But that’s how it works when there’s money, you can do anything. And when there’s no money, you can’t even convert an open balcony into a room.

Whenever I get to Acre nowadays I enjoy every moment. The city is laid before me, a Jewish Israeli, rolled out like a red carpet: cheap hummus, quasi-hypster cafés with Arab chic and affordable prices, an open-air market that takes me back to the days of my big post-army trip. A perfect getaway for hardly any money. The other week I went with some friends on a dream vacation in Acre, and that’s exactly what it was. We walked around like royals, surrounded by locals. Overcrowded locals, packed together, their businesses getting shut one after the other to make room for Jewish-owned ones, their homes coming apart before their eyes and there’s nothing they can do about it.

And when your home crumbles before your eyes, your children are raised without a private room for themselves, and the city you’ve loved so dearly is turning into a tourist site, turning you into just another tourist attraction, there aren’t that many options left. Arab residents leave Acre and move to nearby towns and villages. There they can surely build a fancier, warmer, healthier home, within a relatively homogeneous community. But then, once again, it means wandering away from home, away from memories, leaving the land where they had raised their children. All that is the lesser evil. In many other cases, residents are simply evicted under the guise of “conservation.”

There’s a good story to be told of two adjacent houses, located right behind the famed Uri Buri restaurant, which made headlines last week when it was set ablaze. The two houses are entirely identical in terms of structure and history. One of them is owned by Amidar and populated by a Muslim familiy, while the other was purchased by a Jewish investor seeking to turn it into a boutique hotel. The former, decaying and crumbling, is slowly but surely falling victim to a silent war – when will its residents despair and leave? The latter is renovated, standing strong and handsome, awaiting its tourists.

And what about data? Between 2013 and 2018 nearly half of Acre’s Arab residents – 40% of them – left the city, gone in a dust cloud, surrendering their homes to the city’s development and conservation. Conserving its stones, that is, because an Arab city devoid of its residents can’t really be conserved.

Meanwhile, the Garin Torani (a religious Zionist settlement community, which we’ll get back to later on in the story) has taken root in Acre and started growing. Other garinim, ideologically motivated groups, not only religious at this point, began taking over large swaths of the Old City, harming the already delicate fabric of life in the community of lower-class Arabs and Jews. Raising flags, marking all sorts of marks, and overall, arriving with a clear agenda. “Us” and not others. The new landlords, foreign to local traditions, brutally crush the sensitivity required by this type of city.

Israelis regard Acre as a prime example of brilliant co-existence: The Arabs work for us, laying down cultural riches, food and atmosphere on a gold platter, for us to rake in the symbolic (and financial) wealth. Arabs regard it as a prime Israeli model of circular dispossession, repeating itself over and over again. First in 1984, and since then in tiny pulses, again and again over years. They are crushed under touristic ventures, pushed aside and out of their homes, watching their beloved city change beyond recognition. The torching at Uri Buri is a literally burning symbol of this whole story.

You won’t be hearing this story on the news or in TV studios bursting with analysts, filling airtime, even though in 2008, too, the sounds of similar protests caught us – much like now – off guard. Either way, this story serves as the emotional, personal and – undeniably – nationalist foundation upon which frustration builds up, and from which desperation bursts out in the form of what we Israelis experience as an explosion of violence. If you will, like I opened this text – let’s see you try removing me from my home.

לוד اللد Lod

Lod is one of the oldest cities in historical Israel. There’s a lovely tale, one of more than a few tied with its history, a tale about jealousy. Legend has it that the residents of Lod were jealous of their neighbors in Ramle for their whilte tower, erected about 700 years ago along the main route from Jaffa to Jerusalem. The city dwellers took up the issue with the local qadi, who realized that was an important opportunity to teach them a lesson about jealousy. He told them how they could attach rubber ropes to the tower and pull it all the way to Lod. And so they set out to execute the plan, pulling the tower all night; when they felt the rubber pulling and stretching, they thought the tower really did move. By the time the sun rose they were so tired and disoriented that they thought the tower had made it to their city. Only later, when the sun reached its zenith, they came to realize the tower didn’t budge. The qadi then told them: “Those who wish to bring a mountain closer must themselves go to the mountain.”

This tale might sound a bit silly to anyone who, unlike me, didn’t grow up in a family that lives on silly tales that only make sense one day, hopefully, as life happens. But I read this tale – which I once incorporated into a text I wrote about urban legends for tourism and travel magazine Masa Acher – and bitterly smile to myself. How graceful and sensitive the moral of this story is. If you want the mountain, go there. By force you only get more violence.

Lod has been at the core of the latest unrest. Jewish and Arab rioters as if working together, united against anyone seeking to return calm to the city, united in wreaking havoc. The horrifying sights of synagogues set on fire trigger a collective Jewish trauma. And then, during a funeral procession for a man and his daughter, killed by a rocket fired from Gaza, Jewish hooligans show up, looking for victims to beat up.

In the many, but also superficial, media interviews recently from Lod, Arab residents try to convey a complex message, mentioning the Garin Torani, but every time it seems to go unnoticed by interviewers and broadcasters, who never seem to pick it up. Just over the weekend I got a video clip showing several men standing together in Lod. The first, an Arab, says the Garin “comes in and ruins our city. We’re blood brothers. We eat and drink together, we’re happy and sad together.” He then turns to the man standing beside him and utters: “Nissim, do you have anything to say?” Nissim, a Jewish man, says that man is like a father to him, as a third person adds: “Let’s make the situation calm, all together. Anyone who can, from both sides, pitch in and make peace between everyone, man. Here, we have each other’s back.”

So what is the Garin Torani all about? According to their website, they’re on a true mission. Ever since this group arrived in Lod, the city has been developing and growing at record pace. Money is being funnelled in, the city is rejuvenating, schools are getting better. That’s all good news to us, the Jewish Israeli society. But just like in Acre, where the price to pay for development was the Arab residents’ departure, Lod’s Arab residents undergo a complex, painful process.

Lod had been populated by less well-off residents, both Arabs and Jews, and then the Garin, flooding the city with exuberant ideology and zealous motivation to “change,” brought with it more affluent residents and education budgets at a never-before-seen level for the city. The local Arab narrative talks of being pushed out in recent years by the same infamous settler group and by the new neighborhoods built on the outskirts of the city, at the expense of the Old City’s residents. Keen viewers of Israeli TV might remember Lod being mentioned during the final season of My Successful Sisters, where the story of a local youth center was told, recalling a lengthy fight over it between the Garin and the city’s Arabs, who couldn’t use the center and join its activities.

Still, many Jewish Israelis – some of them raised on religious Zionist ideologies while others are non-Orthodox or non-practicing Jews who may share nothing with the Garin apart from tradition – move there for financial reasons. Lod now offers the perfect combination of convenient housing prices, a good location at the center of Israel and quality schooling for children. For young Jewish families, it doesn’t really get any better than that. For the Arabs, clearly, it doesn’t pan out so well.

Beneath the surface, there’s another story. Fida Shehadeh, a Lod council member, went on a panel discussion last week on Kan public broadcaster and talked about messages she was receiving from Arab women in the city who experience violence by Jewish thugs. The anchorwoman, Romi Noimark, asked her why it was her, rather than the police, who was getting these messages. Smirking, Shehadeh explained: “The police is the last place you’d turn to in Lod. It’s been a decade now that we have no personal security. Now it’s just happening in real time for the Jewish society to see, so everyone’s disturbed.” A few days later, the news reported the release of Jewish suspects who shot dead an Arab man. The charges against them were downgraded from murder to negligent homicide, a move pushed for by Public Security Minister Amir Ohana in a series of terrifying tweets, at the height of a civil war, also calling on Jews to arm themselves. It begs the conclusion that there is, indeed, selective policing and law enforcement in Lod, keeping Jews safe but failing to protect Arabs, in times of war but also in times of calm.

Over the past year, some more things added fuel to the burning fire of Lod’s “co-existence.” The city’s mayor, politically affiliated with the religious Zionism, decided to freeze construction in the city and threatened to deport Arab residents, citing repeating incidents of violence (It’s hard not to mention here the roles played by the police, who fail to collect unregistered and illegal firearms, or Minister Ohana, who has left the city completely abandoned). Making his threat, the mayor made a distinction between Jewish and Arab criminals, claiming the Jewish ones have some compassion in them while the Arabs have no inhibitions. Later on, he hosted lawmakers from a newly founded far-right party, aptly named Religious Zionism, for a tour of Lod’s Arab neighborhoods, as if they were a sight to be observed rather than the homes of actual people.

This brings us back to sensitivity, such an important value totally missing from national, as well as local, government in Israel. Crime in Lod disturbs all, Arab and Jews alike, but the mayor uses it to widen the gap that separates the two communities. Meanwhile, the Garin Torani community gets more budgets, apartments, quality education and convenient lives at the expense of the Arab residents. The fabric of life in Lod as we know comes crumbling down. A relative quite, under which the national rift between Arabs and Jews has been bubbling, is getting more and more blurred by the massive presence of ideologically motivated Jews who see themselves as superior and see a dire need to “Judaize” the country, including Arab neighborhoods populated by Israeli citizens who had already experienced dispossession. Arab trauma in Israel can also be triggered.

That insensitivity was magnificently put on display during that Kan panel discussion, after Councilwoman Shehadeh spoke almost in tears of her beloved city, where she was born and raised: “I don’t know any other model for a city. I do know it’s not the most ideal city for co-existence.” Prof. Yoram Yovell, invited to the panel as the “national psychiatrist” meant to calm everyone down, interrupted: “But the hummus is pretty good.” I thought I was imagining; the essence of Jewish condescension and disdain for the hardships experienced by the Arab society in Israel. Right wing, left wing, with a kippah or without, Jewish Israelis are asking Arabs: Be hummus. Just don’t get any ideas about owning homes.

So Jews shouldn’t live in mixed cities? No, they can and should, but a nationalistic takeover that knows no bounds must be reigned in. It’s not about “what,” but rather “how.” How do you join an existing community? Let go of the rubber rope and stop trying to pull it closer to you. Some humility would help.

חיפה حيفا Haifa

They talk about the Wadi Salib curse. When in 1948 the Arab residents, many of whom high-class intellectuals, were driven out of this Haifa neighborhood, one of the older ones spat out a curse, wishing for nothing to grow in that now damned place. Indeed, since Jewish Moroccan immigrants who were housed there in the 50s left it, in the wake of a pioneering nonviolent struggle that raised the banner of ethnic power relations within Israel’s Jewish society, Wadi Salib’s beautiful houses, decorated with arches and high ceilings, have been abandoned.

Looking back at that curse, nothing really grew there since then. One failed attempt to redo the neighborhood followed another, until in the early 2000s a new project was launched, with a gaudy name: Sally Valley. The “B” was dropped from the name, the Arabic wadi was turned into its English equivalent, giving off a saccharine air of foreign, Western lands.

The spectrum of dispossession in mixed cities is wide. One end of it is driven by a racist, nationalist ideology, like in Lod, while the other by urban development and tourism, but all across this spectrum, the key issue is left unattended: the status and rights of the native Arab minority in Israel.

Haifa has a strong Arab community, both financially and in terms of education. In Haifa, contrary to some other mixed cities, multiculturalism is being celebrated over and over again, seen as one of the city’s strong points. Yet under the surface, much like other mixed cities, power relations are abuzz, changing and shifting the delicate balance.

Here, too, like in Acre and Jaffa, state-owned housing company Amidar plays a leading role: In 1948, the Wadi Salib properties came under Amidar ownership. Starting in 1956 and following the Wadi Salib protests, the buildings were shut and the neighborhood became an urban black hole. The solution the state pushed for was privatizing ownership and effectively selling the houses off to private investors. The deserted, beautiful buildings were sold to 14 investors at extremely low prices.

The municipal zoning plan for Wadi Salib, much like other conservation plans, completely voids the space of its historical and political context, turning the remnants of the 1948 war and Palestinian trauma into nothing more than oriental decorations.

Haifa’s story is a complex one, but the story of Wadi Salib alone – just one of the city’s many neighborhoods – is enough to teach us a very interesting lesson about the Israeli perception of such a space. This isn’t about physical dispossession, removing residents from their homes (although these things are happening in other parts of Haifa), but dispossession of essence, of narrative. By adopting Sally Valley for name, it has already been turned from a local, native neighborhood into a universal one. “It’s marketable and it’s emorphic,” says Orwa Sweitat, a doctor of urban planning and member of the City of Haifa’s Buildings and Sites Conservation Committee. “It is as if the neighborhood has no roots. That way, you can appropriate it, change its image and totally empty it out politically.” He mentions Jaffa; there, like here in Wadi Salib, it started as an artist colony.

And so in 2014 galleries and art studios started popping up around the Valley. Owners handed over their properties in exchange for clearing their municipal tax debts, and Haifa’s artists got free spaces. The move never really became a success on any level, but Sally Valley kept on being built, without any plans for community centers, schools or any sort of communal infrastructure. “This is physical dispossession that is reshaping the place – and its future,” concludes Sweitat.

Haifa’s downtown, however, is seeing similar processes to those unfolding in Acre: Some 40 percent of the residents of Wadi Nisnas, for example, are protected tenants from underprivileged communities, living in Amidar housing. That is, they can’t renovate their houses, and Amidar lets them run down – as can be seen elsewhere in Israel in Amidar projects, often regardless of the residents’ nationality of religion. And then at some point the houses are deemed too unsafe to live in and Amidar issues an eviction order. By law, there are 11 justifications that may be employed in ending protected tenancies. Two of them are widely used in Haifa: public interest and safety concerns.

All the while, Amidar is also selling warehouses and storage spaces it owns to private investors, who demolish the rundown buildings and replace them with high-rise ones that appear almost foreign to the texture of Arab-style houses that surround them. Every such “private” project changes the neighborhood’s character. Planning is aggressive, disrespectful, exploitative – like an elephant in the china shop of delicate relations, or a mine field of collective traumas.

יפו يَافَا Jaffa

Jaffa has been making headlines over the past weeks, with countless demonstrations and violent incidents involving its Arab residents and the new ones, members of the Garin Torani community. Facebook groups I’ve joined when I lived there have been teeming with commotion: “It’s the Arabs’ fault!” “The Jews are to blame!” “The Garin Torani!!!”

A comment to one of those many posts was incredible: A young secular Jewish woman, resident of the city, wonders whether in fact this whole process began a long while ago. Could the foundations of the swift gentrification Jaffa has undergone over the past couple of years have been laid some two decades ago, when conservation and renovation work ended and Tel Avivians started moving en masse to the Arab neighborhoods of Jaffa? Could that woman, who sees herself as a partner in a life of co-existence, have served as a catalyst for what’s unfolding now?

Orwa Sweitat paints a complex picture: “The Arabs in mixed cities are stronger today than they were before. They’re influential players, both politically and socio-economically. They’re no longer the helpless, dispossessed victim, but certainly experience various processes of discrimination and prejudice, compounded by ideological and financial motives. Alongside that, Arab residents’ status in those cities is changing and reinforcing due to the duality of two broad-ranging processes: One of the hand, resistance and claiming rights, particularly concerning cities’ historical centers, and on the other hand, integration.”

Jaffa, which constantly changes at different paces, is a great example. The first major shift occurred with the establishment of the state, when rich Jewish artists purchased the Old City plot to stop the Israeli army from blowing up its buildings, facing the sea, as they did in Tiberias’ Old City. The second pulse came with a bourgeois flow into Jaffa and the development and conservation efforts that ensued, heralded by the arrival of wealthy investors to areas like Andromeda Hill.

The Garin Torani’s arrival is another step, out of God knows how many. The ideology of “Judaizing the land” doesn’t lay bare here. There are clear financial and touristic motives, all sorts of things that could easily be accepted as “good for all of us,” but we must pay attention and see who always ends up on the losing side. The case of the Muslim cemetery right next to the affluent Noga neighborhood in northern Jaffa is an example of that. A spectacular architectural plan was designed for it, spurring a wave of demonstrations protesting it in 2020.

I lived in Jaffa for three great years, and moved out not that long ago. The city completely changed around me by the day. When construction started for a light rail line and housing prices soared beyond any reason I moved to Bat Yam, further south along the Mediterranean coast. About a year ago, I was driving my scooter on the way back from work as a bartender in one of the bars at the Flea Market area when I passed by the house I used to live in. The neighbor from across the road, a young Arab man I would see every morning and every evening when I still lived there, stopped me. He told me that for months police have been stopping guys like him during the day and at night. “They don’t want us to feel at home here,” he told me. It made a lot of sense to me. It wasn’t long after that that a wave of protests by Jaffa’s Arab residents broke out.

The way the Tel Aviv-Jaffa Municipality reacts at the sight of potential profit isn’t new; we’ve all seen the injustices done by it to the residents of Givat Amal and Kfar Shalem. This city will go a long way to realize real-estate potential, and if so far the takeover has been trickling down slowly – a hotel here, another building there – this year it exploded. The city lost its patience: Why aren’t Arabs leaving? It may not be as simple as they had hoped.

Indeed, Jaffa has been developed at record pace over the past two years. The light rail that will connect it to Tel Aviv like never before, put together with a tamed Arab feel at the very heart of the Gush Dan metropolitan area and breathtaking conservation buildings and stunning beaches, brought many new inhabitants. The rundown neighborhoods of southern Jaffa turned overnight into fancy ones; the deserted beaches were suddenly filled to the brim with parasols carrying the Tel Aviv city’s logo, and manners and niceties stopped being part of the effort to force Arab residents out. After two decades of sluggish gentrification, consistent yet slow departure of the city’s Arabs, about 800 eviction orders were issued. Time’s up, get up and go.

The eviction orders for Arabs living in Amidar-owned apartments should be seen in the context of the Garin’s activity in Ajami – a neighborhood that up until a decade ago no one dared coming anywhere near it, not even to develop infrastructure – and the violent clashes between Jewish and Arab youth all across the country and all over TikTok. The greater historical context that Jaffa (and the entire country) holds is at the bottom of this pressure cooker, but even without it, it’s enough to understand that 800 eviction orders handed out to members of a certain community, after decades of creeping expulsion from the city they were born and raised in, are enough to make it boil over.

Take Jaffa – the beating heart of the Israeli and Arab centers – together with identical processes in cities near and far, like Acre, Lod and Haifa mentioned above, and together with the appalling eviction of families from the homes they long lived in in Sheikh Jarrah, with a stamp of approval and encouragement by the Israeli law. In all cases, within Israel’s 1967 borders and outside of them, Arab families are replaced with the help of Jewish money. It’s hard to claim innocence at this point. On top of the clear financial motives, there are ideological motives of a group in Israeli society for whom, as Khen Elmaleh put it, “any trivial action in life (like living in a house) comes with ideology,” making it impossible to claim innocence by now.

It should be said: Each individual settler, each individual citizen moving to a new home probably doesn’t expect and doesn’t hope to get there, but putting all things together, even the best and purest of intentions become part of a comprehensive policy of dispossession, in the north, in the center and in the south. We, Jewish Israelis living here, have become pawns in a policy game, and we’re also the ones paying a price.

So do you condemn?

When I was a teacher-soldier at the Nahal Brigade a massive fire broke out on Mount Carmel, claiming the lives of 44 people. My unit was taken from the boarding school we worked at to help where we were needed more. One of those places we were taken to was a different boarding school on Mount Carmel with a group of teens no one knew what to do with. They were evicted as children from Gush Katif, a cluster of Israeli settlements in the southern Gaza Strip. Once uprooted, they couldn’t regrow their roots; a profound human tragedy pinned to a national conflict whose necessity I don’t fully understand.

What happened in Gush Katif in 2005 was terrible. I remember to this day the heart-breaking images of children grasping at whatever is left of their homes. Whether or not I agree with what brought them to settle there in the first place, I can understand the longing they hold in their hearts. Home is home is home.

Fortunately for us, Jews evicted from their homes, even with brutal violence, enjoy at least some backing from a Jewish state that at least in principle is meant to find solutions for them. It doesn’t always happen and Israeli bureaucracy is often a death trap for those unlucky ones born on the wrong side of the money or class equation. Perhaps what remains of the frustration of those days bursts out now in the form of violent attacks carried out by Jews. I don’t know and I don’t understand that situation well enough to be able to link the two. What I do know, though, is that uprooting, for me, means pain. And pain, when goes untreated or uncared for well enough, finds violent ways out.

Israel, naturally, has a right to defend itself. Palestinians in Gaza have the same right. Death and destruction here and there, these lines I’m writing in Bat Yam in between rocket alerts, are accompanied by the faces of the sweet boy from Sderot, of the cute children in Gaza – victims of that “defense” bought in blood. Its roots go deep into processes that have absolutely nothing to do with defense.