Written by

As 2020 draws to an end, Israeli media could hardly be said to display gender equality. Early in 2021, we set out to examine the state of women in Israeli media. In this special series of articles, we dive into the numbers, perspectives and viewpoints that affect the news we consume.

Tel Aviv, 1977: As every Saturday night, Eli Buenos , my dad, arrives at the “Hadshot Hasport” [Sports News] desk on Tushyia st. No 3. to get his hands on the first printed copies, and learn about game results and players performances before the ink had even had time to dry. Jerusalem, 2020: Every news item in the world is a at my fingertips. My smartphone beeps and I’m instantly up-to-date. A quick scroll through various news apps reveals to me not only game results but every possible piece of information on a variety of topics.

The tart smell of ink, the touch of crisp newspaper pages and the discourse created after reading them are a distant memory, or, at best, an experience reserved to weekends. Newspaper salesman, standing at the corners of busy streets, loudly proclaiming the latest scandal in an attempt to convince passersby to buy a newspaper and hop on the information highway, have long become cultural tropes and cinematic scenes, light-years removed from today’s touch screens and push-notifications.

But one thing hasn’t changed: Even today, when we refresh apps, just as when newspapers made their way to us on the paperboy’s bikes, media remained an inseparable part of humanity’s daily life. The oldest profession in the world, if you will. In times of crisis and days of calm, radio accompanies us on the road, current affairs programs serve as the backdrop to our living-rooms, and push-notifications inform us of every small event. Even the clichés still hold true – today’s news is still tomorrow’s fishwrap, even if both fish and paper are digital.

It’s vicious cycle, a medium that produces interest and rapidly forgets about it, over and over, but still has power to influence awareness, perception and power structures in society; in the words of another cliché – the medium is the message. Ever since Marshall McLuhan coined this slogan in 1964, it became one of the most widespread and well known axioms in the world of media. Today we all know that “the medium is the message”. But what about the one presenting it?

“The Pink Collar Revolution”

In Israel’s first years, the number of women in media was close to none. In 1955, only 7% of employees in the six major newspapers of the time (“Yedioth Acharonoth”, “Ma’ariv”, “Ha’aretz”, “Davar”, “Al Hamishmar” and “The Jerusalem Post” were women, as Professor Einat Lachover, of the Sapir Academic College’s School of Communication writes in a research she conducted along with Professor Dafna Lemish of Rutgers University. This might not be surprising, certainly not back then when generals where superstars and national security was at the center of public discourse, pushing women out of it. In following decades (1966, 1976) women still occupied only a small percentage (10.8%) of positions in print media. Even having a woman Prime Minister did little to improve that, and the few women who did appear in media were mainly relegated to women’s sections.

It was only in the late 1980s that women started entering media in significant numbers. This was termed “the pink collar revolution”, (in the vain of a similar term coined during World War II, when women began entering various professional fields). Three decades later, and the “revolution” that was about to completely change the face of israeli media, did not hold up to expectations.

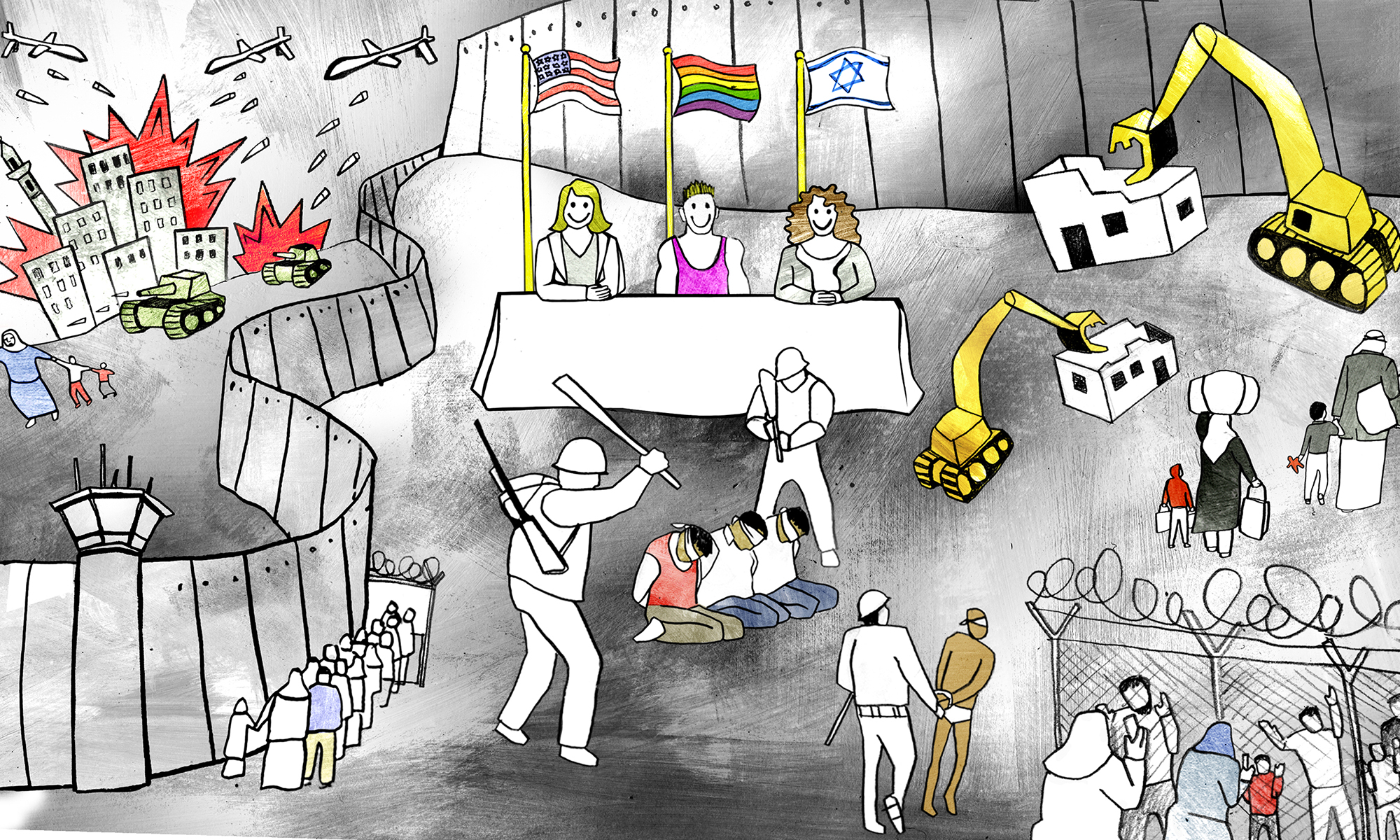

Pic

Source: the “Feminist Journalism and Information Archive” Facebook page. Admin: Nurit Kahana | click to enlarge.

In 1994, Dan Caspi and Yehieal Limor published an essay titled The Feminization of the Israeli Press. It was the first academic work to present the systematic changes to the place of women in israeli media. Caspi and Limor tied changes to the media industry with social changes taking place at the time. They considered the process of feminization of media as part of a wider process in post Yom-Kippur War Israeli society. Caspi and Limor argued that if the trend continues, the industry would become distinctly feminine.

Three decades after that essay, it seems its prophecy of “feminization” fell short of fulfillment. Women anchors are often mentioned in the repeated debate of women in media as representative of the complete gender revolution, but Anat Saragusti, a veteran journalist and one of the founder of “Ta Ha’Itonaiyot” [Hebrew: The Women Jounalists Chamber], an Israeli organization for women in media, notes:

“The very fact we can name each female anchor means there are not enough of them.”

Concerning the same issue, Professor Lachover explains that:

“There is a large gap between the percentage of women on screen and the percentage of women in other roles. Of course, the more we rise in the hierarchy, there are fewer women. But public opinion, even inside the professional milieu, believes this high visibility, which creates a false notion that we’ve already made it. The fact we see women on our screens every day, leading news shows, creates an impression that they define reality for us. That’s not true.”

As much respect and esteem as we have for the women on prime-time television, its still clear that in recent years there has not been any meaningful change to representation of women in media, which is still unbalanced. We set out to examine – where are the women in Israeli media?

The “The Readeress” Gender Index

A “The Readeress” investigation reveals that even today, in early 2021, there is still a very low percentage of women in editing, management and decision making roles in Israeli media – women fill only 26% of these roles in large media outlets, with men filling 74%. While researching this article we reviewed all large media outlets in Israel, examined the names and genders of people in editing, content and data verification roles. For example, in television and radio, the percentage of women in production roles is very high, relative to content related roles. The data imply that women are most often found in “technical” execution roles, rather than making decisions on the nature, type and character of the content itself.

In the recently relaunched Kan 11 channel, 23% of editing roles are filled by women. In production, on the other hand, women comprise 58% of the roles. In channel 12, content editing fares slightly better, with 33% women, while production has 57% women. On channel 13, on the other hand, only few women are at the top of content work, with 17% women in editing roles and 80% in production.

This paints a clear image – behind the scenes, gender representation is unbalanced and unequal, despite the opposite impression many receive from looking at the screen. This is partially supported by the data. When considering only presenters, all channels have nearly equal representation: channel 11 has 47% women presenters, channel 12 – 50% and channel 13 – 48%. When considering reporters, however, the results are not as balanced: only 39% of Kan reporters are women, only 36% in channel 12, and in channel 13, despite merging with Hadashot 10, just slightly over one in four reporters is a woman (26%).

PIC

Percentage of Women in Content Roles in TV Current Affairs Shows

Things are not very different in radio: the news stations we examined had a very low number of women in content roles – contrasted with a much higher number in production roles: in Kan Reshet Bet women are 40% of editors, but 80% of producers. In Galatz women are 25% of all content editors, and 64% of producers. 103FM has 33% women editors, and doesn’t even make up for it with women producers – less than half of producers, only 43%, are women.

In Print? Don’t Get Your Hopes Up

80% of Ha’aretz’s managerial roles are filled by men. 100% for Ma’ariv. In Israel Hayom and Makor Rishon we found 67%, while Yedioth Achronoth, a glimmer of hope, has 55% of managerial roles filled by women. The Editors in Chief of every major newspaper in Israel today are men (Neta Livne in Yedioth Achronoth, Boaz Bismut in Israel Hayom, Doron Cohen and Golan Bar-Yosef in Ma’ariv, Aluf Ben in Ha’aretz and Hagai Segal in Makor Rishon).

Regarding Junior editing roles – Yedioth Achronoth has only 20% women. Ma’ariv does slightly better, but still only 25% women. Israel Hayom and Ha’aretz have comparable rates (27%), and Makor Rishon has a very low one – only 14% of all editors are women.

As for the gender distribution among reporters: Ha’aretz and Yedioth Achronoth present 42% women. Ma’ariv and Makor Rishon has 39% women reporters, and among Israel Hayom regular contributors, only 30% are women.

PC

percent of women in content roles in print journalism

So, it seems reasonable to ask “Where are the women?” not only in managerial positions in media, as only a small percentage of news pages and screen time is occupied by women. But the interesting question in light of this data is “What does all that mean with regards to broadcast perspective?”

This is the News – And Here are the Headlines

Last March, Yifat Media Research and the NGO Hatzlacha published a recent study regarding women in media. The study examined items presented on TV channels for a whole month. They found 16,925 news items in total, which featured 39,010 public appearances by both panel members and interviewees. While more than half of society are women, only 15,179 (39%) of these appearances were by women, while 23,840 (61%) were by men. Certainly progress, but hardly enough in 2021.

Ron Cohen, who conducted the study, says that men are represented on screen almost twice as much as women. He does not refer only to the gender distribution in different roles, but also screen time and number of appearances. The study shows that while men are featured on screen 1,138 times a day, women register only 645 daily appearances. Additionally, Cohen’s findings indicate that male representation peak on critical times, such as when new health restrictions are presented, while female representation peaked when discussing preparations for Passover in corona times. Most male representation is as “experts”. there is also a much more prominent representation of male politicians. These representation gaps can reinforce misconceptions regarding men and women’s roles in society.

Simply put, Cohen connects the prevalence of women in media and their place in Israeli society, a connection reinforced by a study conducted in 2016 by the second authority for television and radio, through Midgam and Yifat Media research, which concluded:

“We find a high visibility of women in items related to education, Consumerism, health, work and Welfare. Men appear more often in more common topics, such as global news, crime and politics. Most women on screen are from the fields of media and entertainment, elected officials, artists and senior management. only a minority of all reviewed appearances featured titles (such as MK, Minister, Attorney, Dr., Prof., CEO or chairman). Of those, the vast majority were men.”

Perach Rotem, Deputy General Manager for Policy & Research in Israel’s 2nd Authority for Television and Radio, adds: “Media shapes the public discourse and consciousness, and we therefore believe it is highly important that it properly express the cultural diversity of Israeli culture. In particular, that it balance and promote proper representation of the various genders. We work to expose the TV and radio outlets under our supervision to the findings of such studies, set goals according to them and discuss ways and means of reaching these goals.”

PIC

Where Does the Gap Come From?

“There are plenty of obstacles, not always deliberate. On the contrary, sometimes they are the result of a lack of awareness. For example, if a bid is worded to target both men and women but there aren’t any women fitting the criteria, it’s a moot statement. No one thinks how it applies to real life.” Saragusti describes bids which may be worded as if to address both men and women, but include requirements only men fulfill. For example, a certain radio station required 15 years of radio management experience for a certain role, an experience no woman in Israel possesses. “Another obstacle,” Saragusti says, “Is expertise definition. For example, for some reason state-security, politics and economics are highly regarded. These are very male-dominated areas.”

The aforementioned 2016 study compared the following time-periods: April-June 2014, April-June 2015, and September-December 2016. These periods were chosen because they were devoid of any military operations, elections, holidays or other events that could bias the data. Ostensibly, they represent a certain baseline of routine, daily life. But in a country were routine is routinely disturbed, is it even possible to study “daily life” and learn something about our media patterns?

The breakneck pace at which we move from military operation to election campaigns to other events on a national scale creates an almost constant state of emergency broadcast. when these “peak events” take place, news channels have a standard protocol; they send reporters to remote locations, call in experts, and spend hours upon hours of discussion on the little information they have. The media protocol of “emergency” creates an hierarchy of reported topics, which determines how much time each topic receives, what titles the interviewees have and how “prestigious” the pundits will be.

“The news hierarchy is expressed in the amount of coverage and the lineup,” says Saragusti “State-security is not necessarily the most important aspects of our everyday life. This raises the question of why “education” is considered a ‘softer’ topic? Why is the security pundit, typically male, more important than the, usually female, welfare reporter? This hierarchy constructs a certain kind of awareness, which separates more important topics from less important ones.”

Corona virus, Saragusti notes, changed the game: “The pandemic is a civil event, not a military one. There was no media protocol in place for it, so media suddenly had much more room for previously unheard voices. For example, female Arab doctors. Moreover, following Corona, many more women are called in as experts, rather than merely eye-witnesses. It reshuffled the deck, but not entirely. Reality is still mediated primarily by men, through a limited worldview. We, as consumers, lose out on other worldviews, other perspectives. Women are not a sector, it’s not enough to have one women in an otherwise male panel. The goal is to bring other content, new perspectives.”

Do Women Really Bring Different Content?

In 1988, during the first Intifada, a young female reporter named Carmela Menashe, rocketed into fame. Menashe started her career as a secretary in Kol Israel, was later appointed crime correspondent, and finally as Kol Israel’s military correspondent. She was the second female military correspondent in Israel (following Tali Lipkin-Shahak), and is to this day the only female senior reporter in the field.

Along the years, Menashe exposed military scandals and whitewash and came to be known as “The soldiers’ mom.” This nickname captures the great revolution she brought to the field: “Carmela Menashe has redefined military correspondence because she considered soldiers’ private lives.” Saragusti says. “By that, she has shown us how much we are missing by treading the same worn path and silencing other voices.”

Keren Neubach, who presents “Seder Yom” [Hebrew for “daily agenda”] on “Kan Reshet Bet” is considered a pioneer in her field. Neubach started her career as an economics and politics correspondent, and in 2004 started hosting shows. She’s been the host of “Seder Yom” since 2008, and won with it the “Best current affairs show” in the 2009 Israeli Radio Awards. Ever since Neubach began hosting the show, news started featuring topics which were previously strictly in the purview of alternative media. Daily struggles, social gaps, and of course – violence against women, became headline news on Neubach’s program, and, as demonstrated by the 2009 award, also on the public agenda.

“Keren Neubach has practically defined an alternative agenda,” Saragusti emphasizes, “by presenting topics not subject to the usual lineup. Carmela Menashe and Keren Neubach are two strong, independent women, working for years, and that’s very impressive. But having only a small number of such example is a testament of poverty, not plenty. We are losing so many points of view.”

“The news are a central source of information and perspective for most people all over the world, even today,” Professor Lachover adds. ”While news is also consumed on social media, traditional channels are still central and retain their importance. We can’t ignore the way consuming news aids us to define and understand reality. If we’re not there, we’re nowhere.”

Both the cited studies and our own research leads to the same conclusion: despite significant changes in recent years, men and their perspective still enjoy a higher visibility on TV screens. It seems that the feminist struggle for the news-editor’s pen is still far from over. The answer may not be only in the number of women on various panels (which did grow in recent years): “The presence of women alone would not necessarily bring something different. Not in terms of the topics we cover and not in terms of our perspective,” Professor Lachover emphasizes. “We have to talk about diversity, not only numbers. That’s our job as feminist activists who understand what it means,” Saragusti adds.

What does it mean? In the following articles we will delve deeper into what these numbers mean. We will examine whether media, the watchdog of democracy, the bearer of the flags of courage, integrity and fairness, can indeed fulfill its role, with the perspective of half of humanity missing from it?.