Translated by Ayelet Silberberg | hebrew version

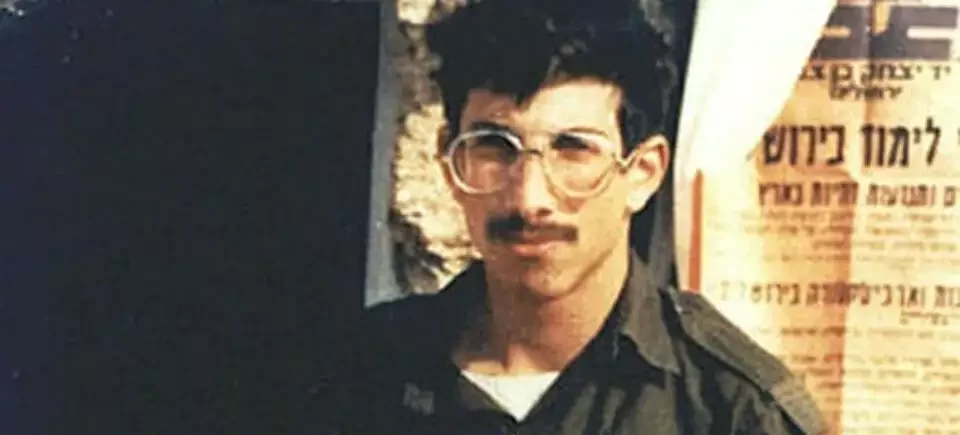

M. is a 35 year old married father of three from northern Israel. He took a break from his active reserve duty for the past 4 years. On October 7th he put on his uniform and went south. In his civilian life, M. is a sexual health educator who works with young men on sexual violence prevention, healthy relationships, and deconstruction of traditional oppressive masculinity.

This is his testimony:

From the first moment it was clear that we were called into something that we might not come back from. We understood that this was not normal reserve duty. We didn’t know anything. For all I knew, I would run into terrorists on my drive south on the highway. And that was it, we went in. Just like that. We enlisted. That was the start of one of the most painful experiences of my life.

I felt foreign. I felt different. I felt like I love my friends, but I don’t want to speak their language. That I’m supposed to express some kind of aggression – and when I do, I scare myself, and I also understand where it’s coming from. There was an enormous conflict inside of me. Everyone around me, their motivation, their reason for getting up in the morning, was revenge, and I felt like that’s the type of motivation that kills you, and I just want to make it home to my kids. No. Want is not strong enough of a word. I refuse to let my kids grow up without a father, on the altar of this thing. In the inner reckoning you have with yourself, I started imagining my kids growing up without a dad, my wife living life without me. No. I refuse to pay that price.

This contract, that you sign when you’re 18, your life circumstances change, but you’re still chained to it. It took me a really long time to understand what was happening to me. I told myself, when the time comes for me to take my things and go home, I’ll go, but as long as I’m conflicted, I’m not moving.

Aggressions of Revenge

When I was 20, as a commander, I would check how my soldiers handcuffed prisoners. I would tell them “If you’re tightening the cuffs because you want revenge for what you think they’ve done, then you’re not being professional.” I didn’t care about speaking out, getting criticized. I was a good and beloved commander. In this war, I discovered that I don’t have that strength inside me anymore. I watched Palestinians being put into the trunk of a Hummer and soldiers beating the hell out of them. I saw soldiers taking their rage out on Palestinians’ property for no reason. And I’m watching from the side and I’m saying to myself “fuck, what am I doing here? Why am I not hugging my kids? Why am I not rebelling against what I’m seeing?”

This thing, it’s this violence that is so blatant and so obvious, and you don’t have any way of rising up against it. It shook me, I’m tortured by it, that I didn’t speak up. That I gave up. That I felt like it was a lost cause. It eats me up inside. That I see this thing in front of my eyes and I can’t find the strength to say anything. And in all that unrestrained violence, where the only thing motivating it was revenge, our battalion commander was the leader. His nickname was “commander TikTok.” He put us in danger during every single moment of this war, for no operational reason. And his deputy, his hobby in Gaza was entering homes and setting them on fire. For no reason. And along the way, he would burn up material we needed for intelligence. He had no way of knowing if there were hostages in a basement, or in an attic. He’d go into every house and burn it down. He didn’t know if there were other forces in the area that could get hurt, if there were explosives that could be set off. Just endangering human life every day, in the most childish manner imaginable. For no reason.

Fear, loathing, and helplessness

Standing in the face of those aggressions, was our division commander. An educator, an amazing man. I think this war took something from him that he will struggle to recover. He really suffered. He was boycotted by his soldiers, they didn’t trust him. He saw everything that was happening and he had no way of responding. It was a very out of control situation, uncontained, severe.

What makes you a popular commander in a toxic environment? What makes people trust you? Not the same things that make them trust you in a healthy environment, one that isn’t flooded with horrors. Where we were, if you didn’t take part in very extreme conversations, politically, you lost popularity. I watched people around me dissolve, fade into a silenced, paralyzed place.

There were a lot of unprofessional and dangerous situations around us. Someone threw a grenade, unclear why. I didn’t know of a situation in the IDF where you shoot and you don’t know what you’re shooting at. I didn’t know of a situation in the IDF where you throw a grenade and you don’t know what you’re aiming for. But here, people shoot just to shoot, and then they yell “appropriate fire.” There is nothing appropriate about it.

I think they were motivated by fear. Incredible stress and a ton of fear. But if you don’t separate between fear and the desire for revenge, people start thinking, “what, I’ll come back from Gaza without an X on my weapon?” In the days of the ceasefire, there was a ton of indiscriminate shooting. Full machine gun magazines. I don’t know what hit and what didn’t. On one hand it’s clear to me we are not committing genocide, that’s not the question here. On the other hand, these are terrified 25 year olds, sitting in some balcony, in some attic, and there’s a ceasefire, and they’re told “don’t shoot unless you see a weapon”. So they shoot out of fear. And then they hit and become heroes. Those are the rules of the game.

If I hear you speaking out of fear…

One time, we went to fill up on gas and there was a really sweet guy with us in the middle of a semi-panic attack. He talked about how he promised his parents he would return safely, and how he’s scared to death, and he doesn’t know what to do. And then this other guy who was with us, who is actually a bereaved brother now, a great warrior, laid into him: “if I hear you talking about your fear, I’ll fuck you up. And if you really feel that way, then get out of here because you’re making all of us weaker by talking like that”. It was a crazy moment. It wasn’t just the first guy who heard it, everyone heard it. And I thought, “wow, bullying isn’t just for middle school, it happens at age 35. If you talk about your feelings, I’ll fuck you up”.

That bully, he was in the same section as me, and he led a clear path of vengeance, with no respect for other views or opinions. He told us that during Operation Protective Edge his friend was having a panic attack and he slapped him in the face. And I thought of how many Israeli soldiers experience panic or anxiety and are responded to with violence. I remembered a situation that happened early in the war, when I went to fix some soldier’s gun and I saw that there was a “red alert” in the Galilee. I realized that my kids are with my sister and that my wife is so far away from me and I totally collapsed. I cried my eyes out in the corner of some armory. Walla, I spilled so many tears there. I was done for. I was there alone. I finished crying, I cleaned myself up and I went back. Nobody knew. If that guy had seen me go through that, he would have slapped me in the face. That would have brought out intense violence from deep within me.

Later I took the guy who had the panic attack aside. I told him “Bro, your parents aren’t sleeping at night. Go home. No big deal.” And when I told him that, I started to ask myself “what are you doing here? You could be one of those dads pushing their kid on a swing right now.” I felt like I betrayed myself. I know I’m not a warrior. This thing, where you die or you take someone’s life, it hasn’t been my story for many years. And I told that guy what I needed someone to tell me.

My kids

There is this norm in the army where you leave your kids and go. You might say “I haven’t seen my kids for a month. I don’t know if I’ll ever see them again”. And it’s normal. Everyone is just ok with it. But me, my skin is tearing. I have to. It’s a “maternal” feeling. Yeah, I know that men go out to protect their home and dad is strong and he has a gun, but it’s tearing me up. And I couldn’t find any space in that environment where I could say “fuck, bro, I can’t. I want to be with my kids.”

One day our company commander got really mad at us. He asked “why are you acting so homesick?” Homesick. Homesick??? That’s something you say to a 19 year old who wants to go home and drink beer with his friends. I’m not homesick, this is existential. I have a continuation of my limbs somewhere up there in the north and I have to go to them. That was the moment I realized I am now on the list of people who might die and it’s totally fine, and to be honest with you, I don’t really care about dying because of myself, but I refuse to accept that my kids’ lives will be fucked up. And it’s a dissonance I could not bridge. I could not normalize it within myself. I only went home twice during my time in Gaza, and both times I looked at my kids and I thought “I’m stuck. I can’t go back there, I can’t stay here. I can’t die. I can’t live. I can’t talk to the guys, I can’t stay silent”.

Watching someone lose it

I found myself dealing with things I’ve never dealt with before, like being mocked for who I am as a person. People could say things to me like “you’re a guy who’s a girl,” or worse: “the way you talk is harming our ability to win” and they mean talking about any doubt, caution, or emotion.

At the start of the war, during the first days, we were in a tsunami of death. It was everywhere. It was in piles, beyond any proportion. None of us ever thought we would see anything like it. It was awful. Our officer, our section leader, actually lost it. I saw it happen in front of my eyes. We were on a night mission, we saw hundreds of bodies, everywhere. I saw that he wasn’t sleeping, that he was stressed out. Sweating. I was next to him and he said to me, “they’re on their way to Jerusalem now, right?” I asked him “who?”, “the Hamas, Nukhba, on the way to Jerusalem”. I told him “No.” And he kept going “my wife and kids are in Jerusalem.” I told him, “Yes, they are safe. You are here. Hamas is there. And they are not on their way to Jerusalem.”, “Oh, Ok.”

I told him to try and sleep, but he couldn’t. He fell flat on his face. He fired shots in the air inside our base… totally lost it. When that happened, the guys immediately started acting like teenagers – when something super real happens, you retreat into sarcasm. They turned to black humor. Blacker than black. I looked at them and I was shocked. How are we not stopping? This person lost it in front of our eyes. I asked to take him to see an army psychiatrist, but because I had left reserve duty for four years, my status in the group was weak and nobody listened to me. They said “come on, leave us alone.” I realized that we were all on a slippery slope of emotional deterioration.

Ok, revenge

There is something about how we fell into this war, that changes you forever. You’re in Gaza and there’s a drone above you and that drone can drop an RPG warhead on you at any moment. And around you, rivers of blood. Massacre. There were days I couldn’t stop myself and I read testimonies from Oct. 7th and about the sexual violence and I told myself “Ok, revenge. Woe the Gazan that falls into my hands.” When you see the pictures and you see the level of devastation and harm, it’s a voice that comes up inside you. With what I was seeing, I couldn’t believe people were capable of doing those things. That doesn’t make me a hateful person, but I can’t see “peace”, and that breaks my heart. It connects to profound existential questions like, for example, is it possible to live here? The soul absorbs so much violence, and that violence doesn’t go anywhere. We received a critical mass of violence, and it’s something we are walking around with.

There is a war, it is an existential war. I go and I fight. And I think that there is something amazing about my ability to acknowledge there is a war and to keep my beliefs intact. We’re in a tragic circumstance, we never wanted to get here, and I think that if men in reserve duty had a wider emotional range, they would be better soldiers, better regulated. The question I’m left with is how can we learn to see the tragedy of our situation, and to be less binary. Not to stay in a mindset of “winners and losers,” but to understand that it’s just painful. To understand that we are broken. Why aren’t we breaking down? Why can’t we meet our pain? Why are we stuck only in the rage?

The protective layer crumbles

During the war, I couldn’t talk to my wife. I didn’t have the words. I really avoided it… I couldn’t figure out what to say, and during phone calls there were booms in the background all the time and my kids got scared and started to ask what was happening. When I went home, on breaks, it was worse than being in Gaza. This thing where I go home, and I find my life there – normative, a guy just living his life – it’s unbearable, it’s a very sharp transition. And it’s painful for me to know this is the model my kids are seeing. My son draws battle pictures and “Daddy, I drew you beating Hamas!” I can’t resolve it. I have this stress that is blurring my consciousness. I have no doubt that it relates to the construct of masculinity, that it has to do with my dad, memorial days, and very deep layers of socialization.

When I was released after two months, my wife looked me straight in the eyes and said, “listen bubi, you are the love of my life. If you put your uniform back on and go back to Gaza, I’m no longer married to you. I’m taking the kids. I can’t live like this. I can’t live in fear for one more night.” It was rough. But it was clear to me that I’m hers. I belong to her much more than to this whole thing. It’s not even a question.

I ended up being released after a very complex situation, socially and operationally. I told my friends that I’m done and I’m looking for another section for reserve duty. I realized that with the battalion commander and his deputy, I could just die for nothing. Not because of a battle for Be’eri, but because of some idiot. So I sat down with my division commander, who immediately understood where I was coming from, and he said “find somewhere else, maybe I’ll do that too soon.” And he encouraged me to go to therapy, not to sit with it alone.

My friends are somewhere between angry and disappointed. They are not on good terms with me. We’ve changed. We used to be a group that got together and would have bonfires and hang out until sunrise, talking. Now our conversations are fractured… the relationship went through something heavier. We’re different now.

I realized there are things from the army that I have to process. My biggest trauma from the army is actually from basic training. This thing, where you aren’t the owner of your own body and your soul feels betrayed, where I hear my inner conscience telling me “This isn’t who you are,” but I go anyway. It’s injurious. It’s a feeling of self-betrayal. You betray yourself and you never forgive yourself. When I would come home from basic training, after functioning like a beast all week, joking with my friends, at home I would shut myself off in my room, my mom would ask what’s wrong and I would say “I don’t have a soul. I’m finished.” In the war I felt that same dissonance with my family and that same feeling of soul betrayal. It’s really heavy stuff. It is possible that the fact I’ve been deconstructing my masculinity made this war more wounding for me. Maybe the more you expand your emotional range, you become more resilient, but you also lose a layer of protection that crumbles, and that doesn’t serve you well when you are in the heart of Gaza, with a bunch of people who have a Nukhba mindset.

I find myself disconnected, in my sadness. I sit on the couch for an hour, sad. My wife also hasn’t recovered from two months of insane worry and caring for the kids… we’re recovering, but we’re going through it together. My soul did a sophisticated thing and replicated the intensity of the war into my life, to get away from the war. I took on tons of work. I don’t have a dull moment and it’s horrible. I have to find a way to titrate, to cancel things, to look after myself, but I don’t have that strength. It’s unbelievable how much this is like war. This thing where you validate your existence through productivity and escape from yourself through productivity… my wife tells me “You’re not in reserves,, but you’re not here either.” This is going to be the story of hundreds of thousands of Israeli men who come home. This is our modus operandi, “I was just in a once-in-a-lifetime war, and my nights are steeped in it, so I’ll go back to the office.” It’s insane.

Mom and Dad

My dad was a career military man. A general, a beast. A very impressive guy but opposite from me in that sense. Sometimes I troll him, and I ask him “Dad, did you and your friends from the Yom Kippur War ever sit down for processing?” and he says “will you stop with this bullshit.” That’s my dad. He’s a unique case. My mom repressed it. While I was in the war, she kept telling herself “I know nothing will happen and he will come back home.” It’s a crazy level of denial.

I felt that in my relationship with my parents, there was a big rush to get back to normal, and because of my wife and kids, they took a step back. But I wanted my mom to hug me, and I thought “mom, forget about my wife and kids for a minute. I was worried about us.” My wife is the wife of a reserve soldier, but where are my parents? And when you get back, everyone is supposed to be euphoric at your return, but that euphoria meets these huge pain and sadness points within you. And you can’t deliver the goods. When I got back, we had a family weekend together. I felt foreign and disconnected. I felt peace only when I was sitting with heartbroken people. When I sat with people who were euphoric about my return, I was like a fish out of water.

I’m still sitting with everything. I’m dysregulated. My internal dialogue is intuitive, not concrete and coherent like it used to be. Since the war, I feel a lack of control, a lack of direction. In the past I was very organized, and now I don’t know where I begin or how I end.

I feel like I just told you so much, and I hope my words will validate the experiences of other reserve duty soldiers. I know that putting words to your experience can be soul saving. For example – on Oct 7th we were scared, we were surprised, we were taken hostage, we were not functioning the way we wanted to. Where is the leader who will come and tell us “Your heart is shattered? So is mine. What have we come to, this is madness…”

Validation. There is nothing like validation. It sets us free.